Boots that belonged to invading Russian soldiers are displayed as part of the exhibition “Ukraine — Crucifixion” at a national museum in Kyiv. (c. Martin Kuz)

Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022. The Russian dictator assumed — along with a good many Western leaders — that his army would conquer Kyiv within a week. From the Kremlin to the Pentagon, the received wisdom held that Ukrainian troops and civilians would wilt and possibly kneel before the reputed might of the world’s second-strongest military.

Nov. 19 marks 1,000 days since Russian forces crossed the border and entered a reality that neither Putin nor the West anticipated. The pre-war assessments of Moscow’s enormous military advantage never considered the strength of Ukraine’s collective will. Caught within Europe’s largest land invasion since 1945, besieged Ukrainians responded with fierce resistance to the enemy and profound compassion for their own, bound by a shared love of country and the desire to live free.

Traveling across Ukraine during the past 32 months has exposed me to their dauntless spirit, their resolute humanity. As Putin refuses to relent and the West’s support turns uncertain, as the death toll rises and the destruction widens, these images offer glimpses of a people weary but still unbowed after a thousand days of war.

At the invasion’s outset, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians from the eastern two-thirds of the country fled west to the city of Lviv. At the main rail station, desperate to escape to Poland and other nations of refuge, they pleaded with conductors to board trains already overflowing with passengers. Here a conductor apologized to people on the platform as he explained that they needed to wait for the next train. When he closed the door, he brought his hands to his face as if in prayer, his anguish apparent. (Click on photos to enlarge on website.)

Valeriya Portnianka and her son, Matvey, arrived in Lviv from the eastern city of Kharkiv, where they spent 94 hours in an underground subway station as Russian missiles and rockets thundered down. After a 22-hour train ride, mother and son prepared to board a bus to Warsaw. Recalling the bombing of Kharkiv, Valeriya said, “It was a feeling of dying while you are alive.”

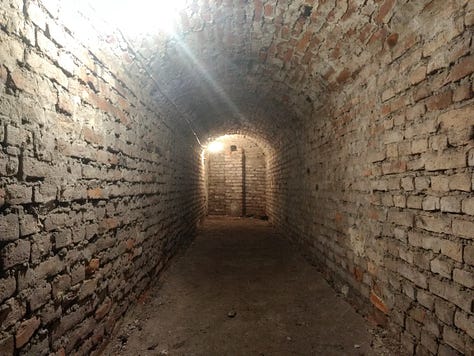

Left: Local officials reopened underground bomb shelters in Lviv that had been closed since soon after World War II. Middle: Sergiy Petrov welded together metal beams to form anti-tank obstacles. Right: At a donation hub, residents dropped off empty glass bottles that could be used to make Molotov cocktails. (March 2022)

The devastation in Ukraine extends to all points of the compass. Left to right: Destroyed apartment blocks in the Kyiv suburb of Irpin (June 2022), the northern city of Chernihiv (June 2022) and the eastern city of Izium (February 2023).

Russia has targeted thousands of museums, cathedrals, memorials and other cultural sites. Left: A missile strike in spring 2022 gutted a museum devoted to 18th-century philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda in a town outside Kharkiv. Right: A missile attack in summer last year ravaged the interior of the Transfiguration Cathedral in the southern port city of Odesa.

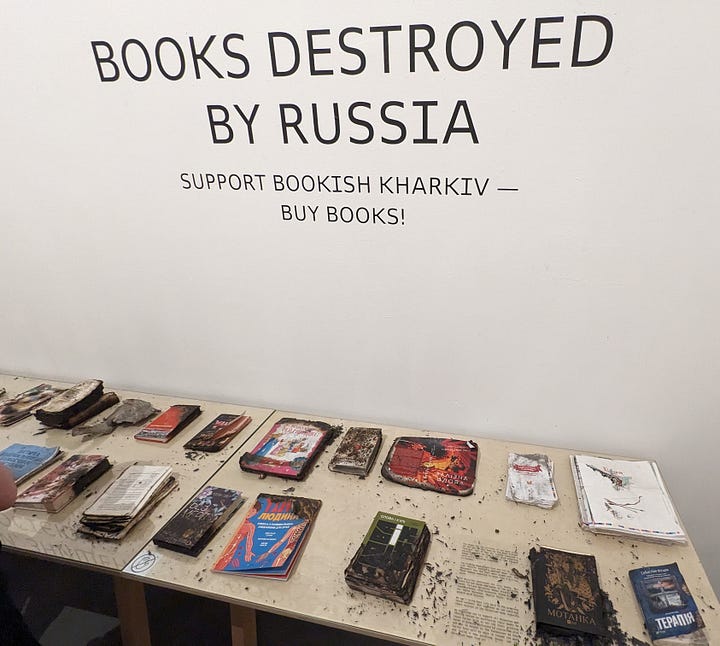

Russia’s bombing of the Faktor Druk printing plant in Kharkiv in May this year killed seven workers and wounded 22. A display at a literary festival in Kyiv a week later included a handful of the 50,000 books burned in the attack.

Russia’s genocidal war has killed some 80,000 Ukrainian soldiers and more than 12,000 civilians — estimates generally regarded as well below the actual toll. Left: A funeral procession in Lviv for two fallen Ukrainian service members in summer 2022. Middle: After liberating the eastern city of Izium in fall 2022, Ukrainian troops discovered a mass grave site — shown here the following February — that contained more than 400 bodies of civilians and soldiers. Right: Graves of Ukrainian soldiers in a cemetery on the outskirts of Kharkiv in summer 2023.

Upper left: Nikolai Kovalenko visited the grave of his twin brother, Misha, in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha in summer 2022, months after Russian troops gunned him down as he tried to flee. Upper right: Olena Shevchenko wept in her home in Izium a year after Russian artillery killed her daughter, Victoria Redko, in the war’s first month. Lower right: Yana Shklyaruk stood beside the grave of her late husband, Ilya, in June 2022, three months after Russian soldiers shot him dead in Irpin as he sat in the car that he used to evacuate neighbors to safety. Lower left: Natalia Rudenko hugged her son, Egor, outside the offices of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group in February 2023. Natalia’s parents were killed by Russian shelling in the eastern resort town of Staryi Saltiv a year earlier. Egor struggled with war trauma — erratic moods, nightmares — after surviving the bombing of Kharkiv as the invasion began.

Thousands of Ukrainian flags, each representing a soldier killed during the war, cover the grass in front of Independence Monument in Kyiv. (June 2024)

Left: A public memorial in Lviv this spring honored Iryna Tsybukh, a journalist, public activist and volunteer combat medic killed in May. Right: Dmytro Kotsiubailo, a revered battalion commander known as “Da Vinci” who was killed in action in Bakhmut last year, lies buried in a memorial park in Kyiv. (June 2024)

The war has displaced millions of Ukrainians from their homes. Left: Lyudmila Mavrych stood inside her flood-ruined house in the southern town of Afanasiivka in July 2023. A month earlier, Russian forces had blown up the Kakhovka Dam along the Dnipro River, and the rising water temporarily submerged dozens of the region’s settlements. Right: In June this year, Luba and Volodymyr Filatov waited at an evacuation transfer point the morning after a Russian artillery strike leveled their home in northeastern Ukraine, trapping them beneath rubble.

Threats abound for those who have returned to villages in the east and south recaptured by the Ukrainian army. Upper left: Vasily Hrushka, shown in February last year, lost a foot five months earlier when he stepped on a Russian land mine buried on his property in the eastern village of Kamianka. Upper middle: Russian troops painted the symbol “Z” on the gate of a destroyed home down the road from Vasily’s house. Upper right: A charred Russian tank abandoned in a field outside Kamianka. Lower right: Shelling ignited a fire that incinerated Maria Kurtnizirova’s home in October 2022, a month after Russian troops had pulled back from her village in eastern Ukraine. Shown in February 2023, she was living in her summer kitchen. Lower left: Andrii Povod stood beside missile and shell fragments that he and a few employees removed in spring last year from his heavily mined farmland in the southern region of Kherson. Russian forces had withdrawn the previous fall. “Here is this year’s harvest,” he said.

The war’s deepening toll has tested but failed to crack the resolve of Ukrainian troops. Left: Viktor Andriyanov lost his left leg below the knee last year when a land mine exploded beneath him while on patrol with his unit in the south. “Ukraine got independence without having to fight and die for it,” he said, referring to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Pictured at a rehab center in Lviv this summer, he added, “So now this is like our independence war, our war of existence. That means we have to sacrifice.” Right: Katya, a combat medic with a unit deployed to eastern Ukraine in summer 2023, grew up listening to her grandparents recall the deprivations that the Soviet Union inflicted on their homeland in the 1920s and ’30s. A century later, as Russia again attempts to eradicate Ukraine, she drew strength from those stories. “Our grandparents and parents protected our heritage, so we must do the same,” she said. “We owe that to them and the generations after us.”

Etc.

— At long last, U.S. President Joe Biden has given permission to Ukraine to strike military targets inside Russia with long-range missiles supplied by America. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer appears poised to follow suit. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz continues to cower.

— Like millions of others, I left Twitter in light of Elon Musk’s war on U.S. democracy (and apparent comradeship with Putin). Connect with me on Bluesky at martinkuz.bsky.social.

— Many thanks for reading. If you’re a paid subscriber, please share your thoughts below in the comments section. And if you’re not, I hope you’ll consider upgrading — paid subscriptions make this newsletter possible. You can also support my self-funded reporting here. Thank you.

Your reporting sheds light on what is a distant and unknown war for many, and you honor the spirit and people of Ukraine. Stay safe and steadfast.