Choose persistence

In this dark moment for Ukraine and the U.S., a dissident’s long fight against the Soviet Union offers a guide to defying despair

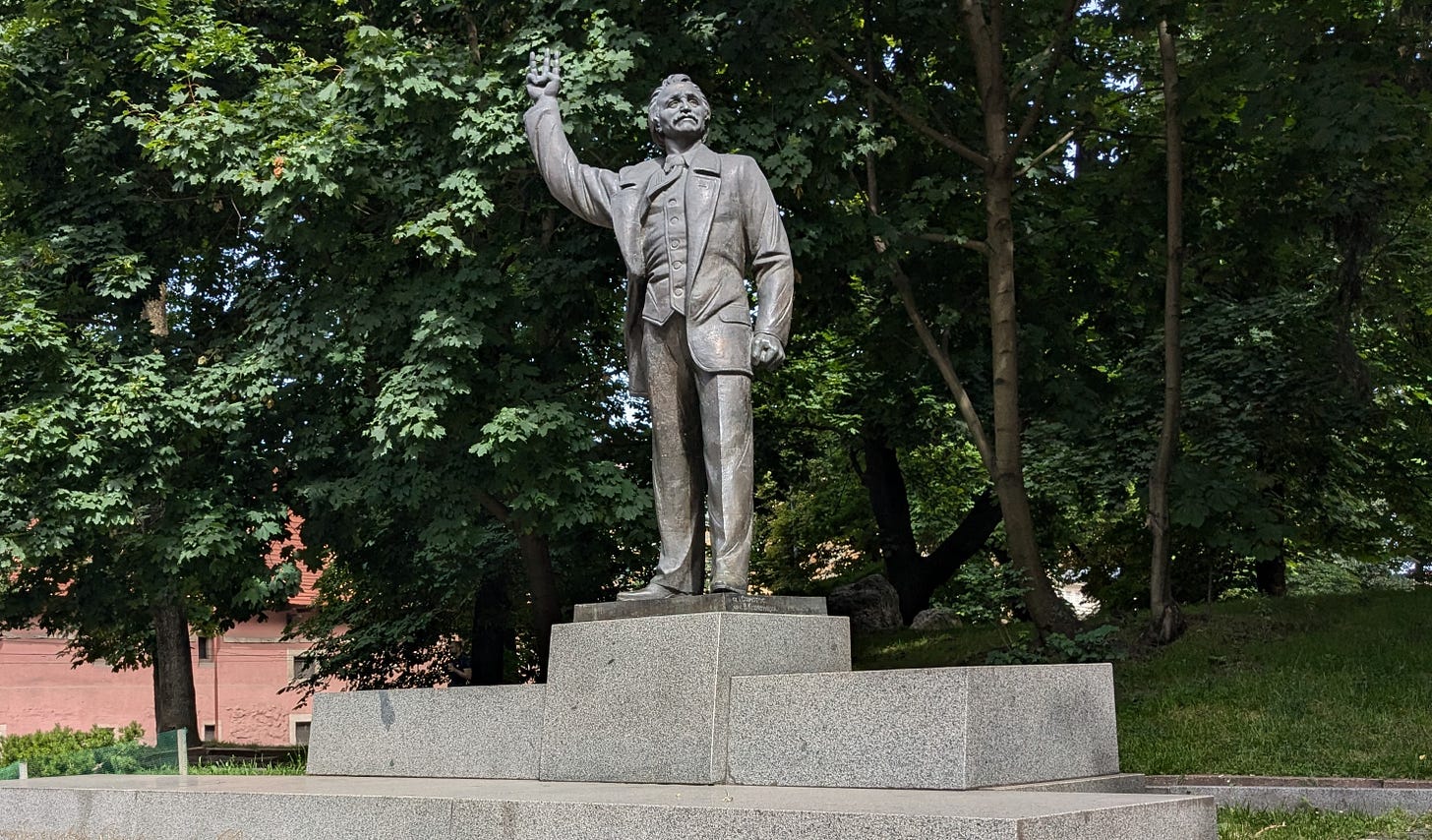

A statute of Vyacheslav Chornovil stands in the western city of Lviv, where he gained a reputation as one of Ukraine’s leading dissidents in the fight against the Soviet Union for the country’s independence. (c. Martin Kuz)

Ukraine begins with you.

The words of Vyacheslav Chornovil surfaced from somewhere in my memory while I doom-watched U.S. election coverage Tuesday evening. The early results made clear that Donald Trump would return to the White House, an ominous prospect for American democracy and a possibly fatal one for Ukrainian independence. As Republican red flooded the electoral map from east to west, Chornovil’s call to action floated across my thoughts, a life preserver I grabbed to keep from sinking into resignation.

Long before there appeared any reason to imagine that one day Ukraine would wrench free from the Soviet Union, Chornovil embarked on a decades-long crusade for his homeland’s liberty. In 1965, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, seeking to root out opposition to Moscow, ordered mass arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals, siccing the KGB on 200 prominent writers, scientists, academics and artists. The crackdown on nationalist expression marked a sharp break with his predecessor, Nikita Khrushchev, who in the aftermath of Joseph Stalin’s reign of brutality had eased censorship in politics, media and the arts.

At the outset of the purge, Chornovil, then in his late 20s, worked as a journalist for a state news outlet in the western city of Lviv. He and two other activists risked arrest to organize a rally at a local theater to condemn what they called “the revival of Stalinism,” staging the first-ever public challenge in Ukraine to the totalitarian regime. Chornovil’s subsequent refusal to testify at the trials of friends and associates involved in the dissident cause earned him harassment from authorities, including house searches, interrogations and the loss of his job.

The intimidation deepened rather than diminished his belief in Ukraine’s right to sovereignty. He turned to the underground press (samizdat), publishing critiques that exposed the Soviet system’s hypocrisies and cruelties. In the work that gained him an international reputation, he wrote a series of pieces about 20 detained activists. The accounts detailed their fight against authoritarianism, the Orwellian allegations they faced and the physical torture that the KGB inflicted on them. An anthology of the stories, smuggled out of the country to Paris and published in English as The Chornovil Papers in 1968, awakened the West to Brezhnev’s purge and Ukraine’s liberation movement.

By then, the security services had targeted Chornovil, arresting him in 1967 on charges of disparaging “the Soviet social and state order.” His 18-month term in a Russian labor camp — he protested his treatment with a seven-week hunger strike at one point — failed to deter him. After his release, he launched a samizdat newspaper in Lviv to document political repression, wrote open letters to Communist Party leaders to highlight human rights violations and established a legal defense committee to aid another dissident.

The KGB detained Chornovil again in 1972 as part of a new wave of arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals. He survived six years and hundreds of interrogations in two Russian penal colonies, where he spent long stretches in isolation as punishment for organizing and participating in hunger strikes and other protests. Following his third arrest in 1980 while still in exile, he served three years in labor camps and remained marooned in Russia for two more, barred from traveling back to Ukraine.

Chornovil’s steadfast advocacy for his country’s freedom during 15 years in captivity and exile earned him a pair of nicknames: fellow prisoners called him General as a show of respect; the KGB labeled him Restless for his inexhaustible energy. In his prison essays and articles, smuggled out by released detainees, he exposed the abuses of Soviet authorities and appealed for support from Western officials and human rights groups. His writings intensified criticism of the Kremlin within and outside Ukraine and drew attention from U.S. President Gerald Ford, Amnesty International and the United Nations, further elevating Chornovil’s profile as an undaunted champion of democracy.

In 1985, with the Soviet Union entering an era of political reform (perestroika) under its then-leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, Chornovil returned home to a hero’s welcome and as a galvanizing force for Ukrainian nationhood. He resuscitated his newspaper and cofounded Ukraine’s first opposition political party, and in 1990, he won election to parliament and the newly formed Lviv regional council.

The next summer, on a day when 10,000 people marched through the streets of Kyiv in support of Ukrainian liberation, parliament declared the country’s independence. Jubilant demonstrators stood outside the front doors holding an enormous Ukrainian flag. Addressing the chamber, Chornovil suggested that his colleagues bring the flag inside, and he led several of them in carrying the traditional blue and yellow symbol into the building, a stirring scene in an old nation’s new history. Days later, the flag was raised above parliament, and by year’s end, the Soviet Union had fallen. The political prisoner turned politician had outlived the regime that sought to silence him.

I share the remarkable arc of Chornovil’s life for two reasons. His courage in resisting an authoritarian state — one that at its dark apex appeared unbreakable — testifies to the irreducible persistence of Ukrainians, a trait that has sustained them throughout centuries of Russian tyranny and Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion. I fear what could happen if Trump, who openly admires the Russian dictator and has vowed a swift end to the war, cuts off U.S. military funding for Ukraine after taking office.

But even in the dire event that American isolationism enables Putin to seize Kyiv — a remote though not inconceivable scenario — I believe the essence of Ukraine will endure. Chornovil’s struggle against the Soviet colossus exemplified an abiding national truth as relevant now as then: Russia will never conquer the idea of Ukraine. The country lives within the minds and memories of its people, whose shared understanding of Ukraine’s history of suffering will uphold their resolve as in generations past. In this uncertain moment, Chornovil’s simple exhortation — Ukraine begins with you — illuminates the self-determination that each person possesses to counter the encroaching darkness.

In a similar respect, his story of unrelenting resistance holds a lesson for Americans reeling from Trump’s victory. An abridged account like this one of Chornovil’s defining experiences can create the illusion of a great man of destiny. But he considered himself ordinary, and he recognized that nothing about his life was inevitable, from surviving prison to watching the Soviet Union crumble.

The General focused his restless energy on matters within his control in an attempt to influence an unjust world even as he lacked any sense of whether his efforts would yield change. His unwillingness to surrender as a point of principle — starting with the theater protest to warn about “the revival of Stalinism” — mirrors the choice confronting Americans as Trump’s second term looms. Every individual concerned about authoritarian rule in the U.S. can decide to persevere against its rise, a conscious act on which the existence and survival of democracy depends. Chornovil’s example illustrates the power of refusing to capitulate in advance to fascism and cynicism alike.

Four months after helping bring the nation’s flag into parliament, Chornovil finished second in the race to become the first president of independent Ukraine. He continued his advocacy for democratic reforms in his writing and political activities and later regained a seat in parliament. In 1999, he died in a car accident now widely viewed as an assassination carried out by allies of Leonid Kuchma, Ukraine’s second president and a former communist, who saw Chornovil as a threat to his re-election chances.

His premature death at 61 deprived the country of a vital national figure who might have succeeded in pulling Ukraine fully out of Russia’s orbit had he lived. Tens of thousands of people mourned him at his funeral in Kyiv, honoring a man who defied despair in pursuing his mission to reclaim his homeland from Moscow. After returning to Ukraine from exile in 1985, Chornovil said, “If I were asked if I regret the way my life turned out, the 15 years I served, I would say: not at all. And if I had to start all over and choose, I would choose the life I lived.”

Ukraine begins with you. America begins with us.

Etc.

— The U.S. election has placed Ukraine and its people in even greater peril, and coverage of the war matters as much as ever. My ability to continue reporting on and writing about the country as an independent journalist relies on the generosity of paid subscribers. So if you’re a free subscriber and you find this newsletter useful, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to paid. (You can also support my self-funded reporting here if you prefer to make a one-time donation.) Please share this newsletter with your social media networks and remind people who care about democracy about Ukraine’s brave fight to survive. Thank you.

How cruel that after surviving torture, imprisonment, and exile in Russia, he died at the behest of another Ukrainian.

The resistance here needs to go underground as well.

This is a great piece about someone whose heroic story most Americans have never seen these many months reading about the dark clouds hovering over Ukraine. People who voted red Tuesday without understanding the massive stakes were not thinking critically, if at all.