Genocide then, genocide now

Ukrainians remember the victims of Stalin’s famine as they continue to endure Putin’s tyranny

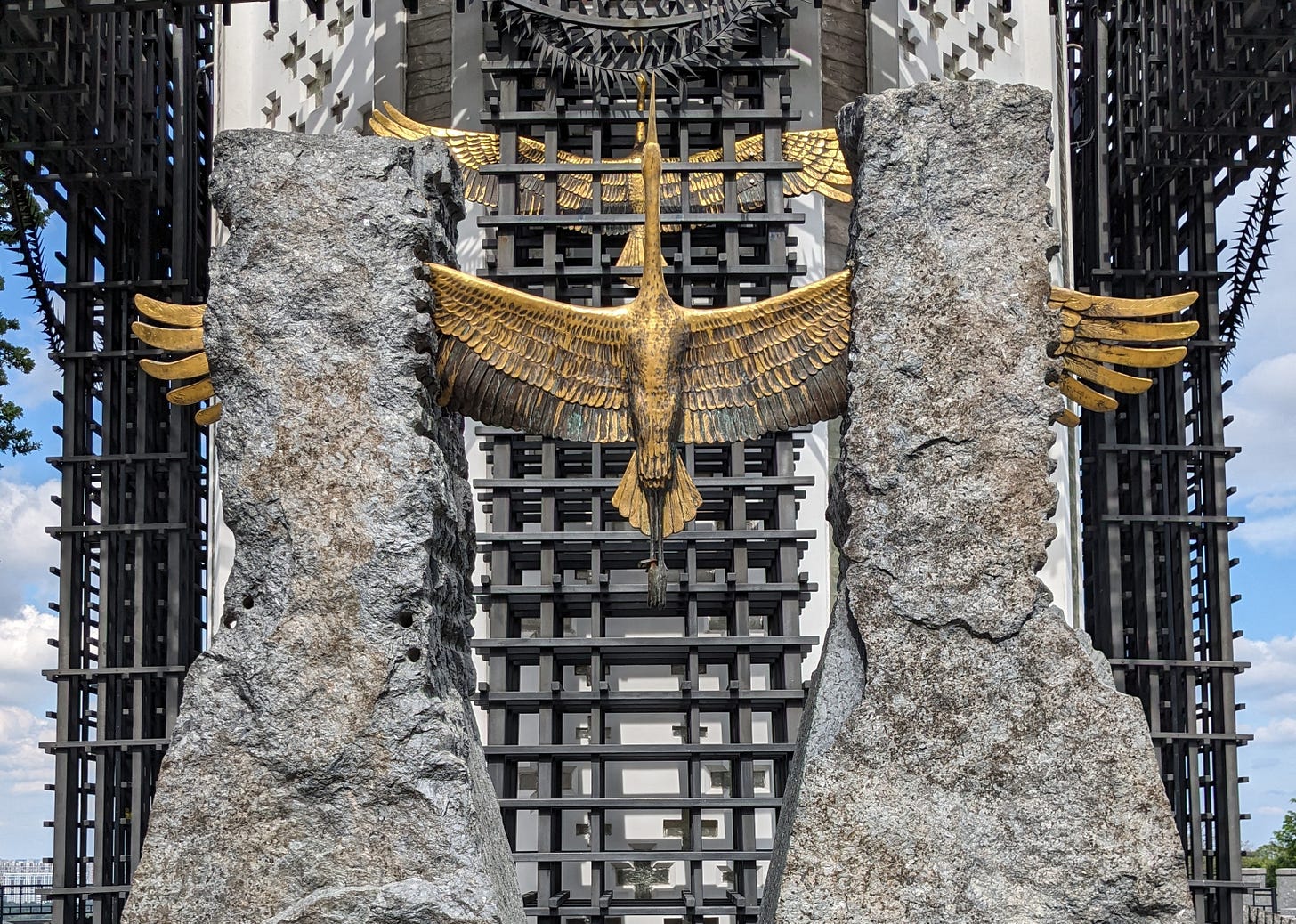

A sculpture of a trapped crane stands outside the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide in Kyiv. In Ukrainian culture, cranes symbolize sorrow for the motherland. (c. Martin Kuz)

Hunger robbed Anastasia Lysyvets of her family one by one. In less than a year, her father and mother, only sister and youngest brother starved to death in their village of Berezan, 40 miles outside Kyiv. They fell victim to a manmade famine engineered by Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin that killed at least 4 million people across Ukraine from 1932 to 1933. After losing both parents and two siblings, Anastasia, 11, and her 7-year-old brother, Mykola, struggled to stay alive, subsisting on weeds, grass, berries, rodents, bugs and bits of wood. The village’s small population dwindled around them as malnutrition turned neighbors skeletal and gray, grinding their bodies to dust.

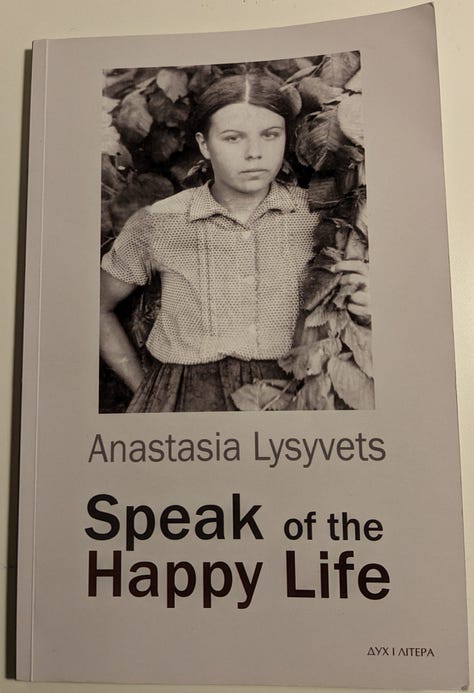

Anastasia recounted the slow-motion terror in a memoir she wrote in the mid-1970s without intending to seek its publication; the Soviet Union prohibited public mention of the famine. A teacher in a rural school, she wanted to leave her two children and future grandchildren a record of the ravaged youth that she and Mykola somehow survived. Her daughter, Natalka Bilotserkivets, found a publisher in Ukraine for “Speak of the Happy Life” in 1993, two years after the Soviet empire collapsed and the country gained independence.

The slim volume offered one of the earliest firsthand accounts authored by a Ukrainian that exhumed the buried truth about the genocide known as the Holodomor, a term that means “death by hunger.” In 1998, Ukraine established a Holodomor Remembrance Day, observed on the fourth Saturday of November. People across the country placed a lit candle in a window of their homes at 4 p.m. today in memory of the millions who perished almost a century ago.

By a quirk of the calendar, the commemoration occurs within a few days of Thanksgiving in the United States, creating an inadvertent contrast between absence and abundance, deprivation and satiation. At the same time, as Ukrainians paused this afternoon to recall a past horror wrought by Moscow, they coped with the renewed Russian tyranny of Vladimir Putin’s genocidal war.

“This invasion has made the topic of the Holodomor more present and relevant because it shows again what Russia does to Ukraine,” said Lesia Hasydzhak, director of the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide in Kyiv. As we walked together through the space this summer, she stopped beside a glass case that holds an embroidered wedding blouse. The garment had belonged to Ahafiia Chub, a young mother who lived in the northern Sumy region and died in the famine, leaving behind her two children and husband. “People are realizing that this is not history repeating,” she said. “It is history continuing, and we are trying to break that history.”

Left: The wedding blouse (rear) of Ahafiia Chub, a mother who perished in the Holodomor, is displayed at the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide in Kyiv. In front is a traditional Ukrainian embroidered shirt that was buried in a jar by a mother in the Kharkiv region as Russian troops invaded in 2022. Possessing totems of Ukrainian culture can lead to arrest, torture and execution of civilians in occupied areas. Middle: A sculpture outside the museum’s entry. Right: Anastasia Lysyvets’ memoir, originally published in Ukraine in 1993, offered one of the earliest firsthand accounts authored by a Ukrainian that exhumed the buried truth about the famine. (Click on images to enlarge.) (c. Martin Kuz)

Stalin ascended to power in 1924 and within five years collectivized Ukraine’s farms to seize command of grain production and exports in “the breadbasket of Europe.” The Soviet state confiscated private land, livestock, crops and even heirloom seeds, and as starvation spread, he deployed troops to Ukraine’s border to prevent its people from fleeing and alerting Europe to their plight. As he amassed a trade surplus that fed his empire’s rapid industrial rise, he sought to crush the national will of Ukrainians and their dreams of cultural and political independence.

Putin has exploited Ukraine’s vast, rich farmland as he aspires to duplicate Stalin’s crusade to extinguish Ukrainian identity and nationhood. His military occupies hundreds of thousands of arable acres in the country’s south and east. The theft of grain and other crops from those areas has enabled Russia — already the world’s top supplier of wheat before the invasion — to enlarge its market share and trade surplus at Ukraine’s expense. The boost to the Russian economy helps propel the Putin war machine as his troops claim ever more territory.

Global awareness of the Holodomor remains far below that of the Holocaust and other past genocides. The Soviet regime’s decades-long effort to conceal the tragedy — aided for many years by a complicit Western press, including The New York Times — contributed to that limited understanding. Putin’s invasion has brought international attention to Ukraine, and the Holodomor museum, attempting to enlighten audiences outside the country, has launched an English translation campaign of oral narratives, books and other materials about the famine.

“Ukraine didn’t really understand the importance of telling the story of the Holodomor to the world. And the world wasn’t that interested,” Lesia told me. “There was never something like the Nuremberg trials to raise consciousness. But now there is an opportunity — a terrible opportunity, but an opportunity — to tell the story of what Russia has done, then and now.”

The museum emphasizes Moscow’s legacy of mass killing in Ukraine by displaying artifacts from the Holodomor alongside items — a burned basket of grain, the charred steering wheel of a destroyed tractor — that capture the havoc of the ongoing war. “But one thing has changed,” Lesia added. “Ukrainians didn’t have guns then, so we couldn’t fight the Russians. Now we do. Now we fight.”

Almost three decades passed between the original publication of “Speak of the Happy Life” in Ukrainian and the first English version that appeared in 2021. The power of Anastasia’s memoir derives from its unadorned descriptions of her family’s suffering as hunger strangles them. Her emaciated youngest brother, Vasylko, resembles “a wax candle” in his last days as he loses the strength to leave bed. The lack of nutrition preys on Anastasia’s doomed sister, Halka, in a different manner, causing her body to swell, her distended legs “heavy as logs.”

The book’s ironic title refers to a comment made to Anastasia in 1934 during the Soviet holiday that honored the Russian revolution of 1917. Then 12 and a top student in her class, she learned from a school official that she would have to give a speech at a public gathering of local Communist Party officials. Sensing her dismay, a classmate tried to comfort her.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “Just remember to speak of our happy life, of how collective farming brought happiness to the peasants and their children.”

Anastasia died in 2011 at age 89, living long enough to witness Ukraine’s rebirth as a democratic nation. In the foreword to the English translation of her mother’s memoir, Natalka recalled a moment from a year earlier, when she came upon Anastasia reading her own book. “She raised her eyes to me and with a look of perplexity mused, ‘Did this really happen to me?’”

I hope that today’s Ukrainian children, terrorized by Russia’s 21st-century genocide, will still live in a free land when they ask that same question decades from now.

Etc.

— Thank you for reading. Please share Reporting on Ukraine with anyone you know with an interest in the country, and if you’re a free subscriber and you like what you see here, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to paid. You can also visit this page to support my self-funded reporting. Thank you.

Thank you, Martin, for being willing to witness and report first-hand the war crimes being committed in plain sight by Putin. It makes me weep to see genocide become such an everyday occurrence that the world (and so much of our media) barely spares it a mention.

An outstanding account of the mass genocide in Ukraine in progress by Russia lead by Putin. He is a butcher