Writing and reading through the apocalypse

The tragedy of war has lifted Ukrainian literature — and identity — to new prominence

The International Book Arsenal, Ukraine’s premier literary festival, drew 35,000 visitors during its four-day run in Kyiv that ended in early June. (c. Martin Kuz)

Every person in Ukraine has faced the dire choice to stay or flee since Russia launched its full-scale invasion in early 2022. Tetyana Pylypchuk made her decision to remain before the first missiles fell. Then as now, she worries less about personal safety and more about national identity.

“Russia has always wanted to erase our culture,” she said. “This is why it is important to be here and go through this time together.”

In her role as director of the Kharkiv Literary Museum, Tetyana, 52, fights for Ukraine with a resolve equal to that of a soldier’s. Rather than drones, artillery and other weapons of war, she draws on the curator’s arsenal of art exhibits, public performances and the written word. “We want to capture our common emotions, our common experiences,” she told me as we walked through the mostly dark museum. Russia’s relentless attacks on the power grid had forced the eastern city to ration its energy supply. “We want to tell our story — the story of Ukraine — to our people and the West.”

Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked war has killed tens of thousands of Ukrainian troops and civilians and displaced millions of people from their homes over the past 30 months. Within that death and destruction lies a truth at once tragic and hopeful: the invasion has lifted Ukrainian literature and identity to a prominence unparalleled in the country’s history.

Interest among Ukrainians in their distinct heritage — obscured by centuries of Russian oppression and propaganda — has surged far beyond the fitful reawakening that occurred in the 30 years after the nation gained independence in 1991. Their hunger for works from Ukrainian writers present and past has spurred book sales and the opening of dozens of new bookstores, sustaining a publishing industry battered by the war. Author events and literary festivals attract capacity crowds, and a deepening curiosity about Ukraine’s origins has brought fresh attention to its founding literary fathers, including Hryhorii Skovoroda, Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Kotlyarevsky.

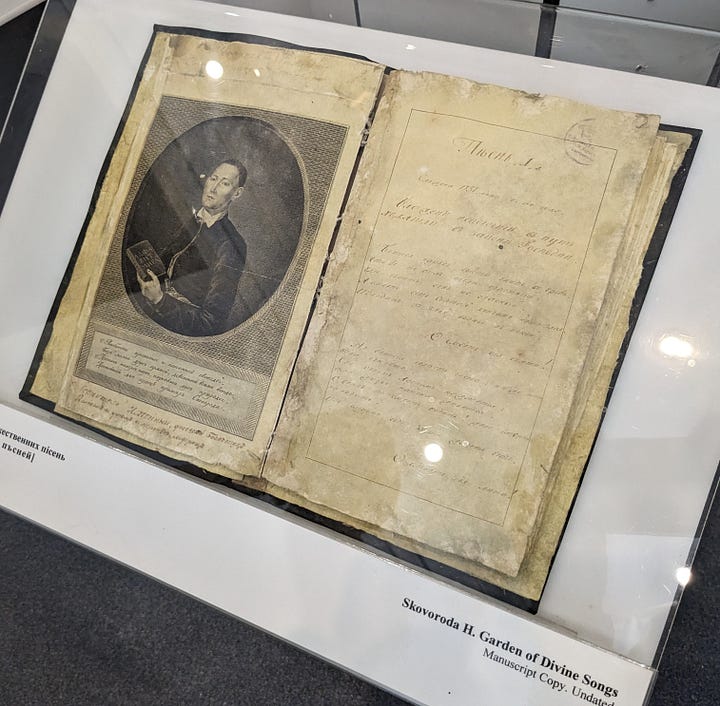

At the museum, tucked away on a leafy side street in Ukraine’s second-largest city, an exhibition on the first floor explores the lasting influence of Skovoroda, an 18th-century philosopher known as “the Ukrainian Socrates.” In his writings, he advocated for individual freedom, universal liberty and the benevolent pursuit of happiness, themes that defied Moscow’s monolithic tyranny in the 1700s and resonate with renewed force in the time of Putin.

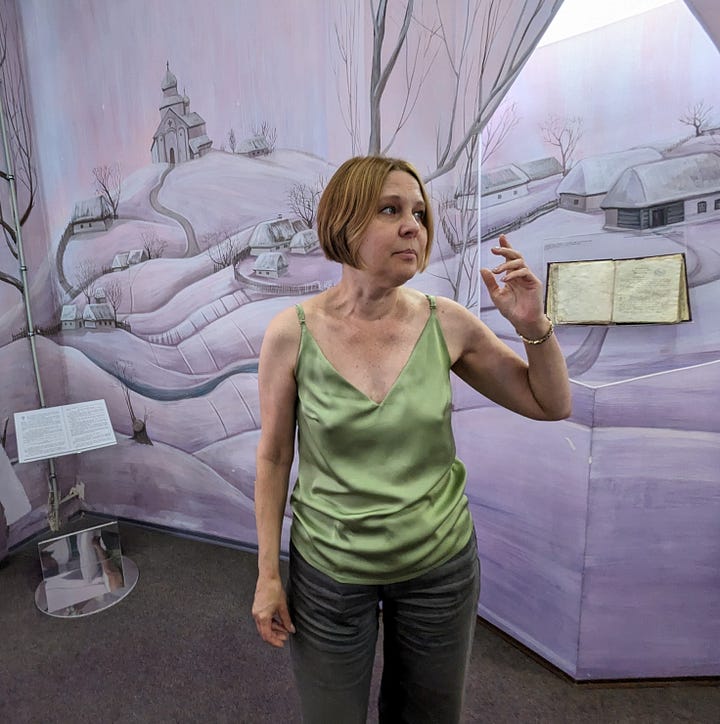

Tetyana Pylypchuk, director of the Kharkiv Literary Museum, stands in a room devoted to Hryhorii Skovoroda, an 18th-century philosopher known as “the Ukrainian Socrates.” At right, a manuscript copy of Skovoroda’s “The Garden of Divine Songs,” a book of poetry. (c. Martin Kuz)

“Because of Russian imperialism,” Tetyana explained, “Ukraine’s culture was seen as a foreign culture even by a lot of Ukrainians. Russia told us what to think about ourselves. So for many people, they are discovering our true history for the first time.”

Another space in the museum focuses on eminent figures of the Executed Renaissance. The term refers to Ukrainian novelists, poets and playwrights who flourished in the 1920s, when they cast off Kremlin censorship after the demise of the Russian Empire.

A short-lived period of Ukrainization during the first decade of the Soviet Union saw a flowering of native literature, political activism and independent thought. Authors, academics and other members of the intelligentsia promoted the Ukrainian idea as they clamored for the country to turn toward sovereignty and the West.

Joseph Stalin crushed the movement in the 1930s. Seeking to suppress Ukraine’s desire for freedom, the Soviet dictator reimposed a brutal policy of Russification to eradicate Ukrainian-language literature, newspapers and textbooks. His security services executed more than 200 authors and imprisoned hundreds more as part of the Great Terror.

“Our Ukrainian writers wanted to separate our culture from Russia and include it in the bigger picture of European culture,” Tetyana said. She has watched Putin, an avowed admirer of Stalin, revive Moscow’s crusade to exterminate her homeland’s people, their history and their collective identity. “Russia lives in this dark past. We use our past for our future — as motivation to go toward a new future.”

Putin’s emulation of Stalin — in malign rhetoric and genocidal deed — extends to a “new Executed Renaissance.” Ukrainian author Victoria Amelina coined that phrase in her foreword to the posthumously published war journal of Volodymyr Vakulenko, a poet and children’s writer murdered by Russian troops in spring 2022.

An outspoken critic of Moscow and Putin long before the invasion, Vakulenko, fearing for his life for his pro-Ukrainian views, buried the diary in his backyard a day before the Russians abducted him from his occupied village in eastern Ukraine. His father and Amelina dug up the manuscript after Ukrainian forces liberated the area that fall; she quickly sent photos of each page to Tetyana in the event that calamity struck while she ferried the journal back to Kharkiv.

Amelina returned without incident and last summer helped unveil Vakulenko’s book, “I Am Transforming... A Diary of Occupation,” at the International Book Arsenal in Kyiv, Ukraine’s premier literary festival. Four days later, as she dined with colleagues in the eastern city of Kramatorsk, a Russian missile slammed into the pizzeria where they sat. She died from her injuries, one of 13 people killed in the strike. Her journal about the invasion, “Looking at Women Looking at War: A War and Justice Diary,” will come out next year, followed by a novel in 2026.

A makeshift shrine was created to honor victims of a Russian missile strike on a pizzeria in the city of Kramatorsk last summer. Thirteen people died in the attack, including author Victoria Amelina. (c. Martin Kuz)

Vakulenko, 50, and Amelina, 37, belong to the ranks of more than 60 Ukrainian authors, poets and translators to lose their lives in Putin’s full-scale invasion — the members of a new Executed Renaissance, in her fateful words. Their sudden absence pushes Tetyana to support and celebrate their works and those of living authors and artists, funneling the energy that arises from her sorrow and fury over the war into what she foresees as the country’s new — and enduring — era of Ukrainization.

“I perceive culture as essential to our identity. We have our own culture, our own heritage, and it is important to understand it is not a culture that exists in opposition to Russia,” she said. “It is our own Ukrainian voice, and we want the world to hear us for who we are.”

Early in the invasion, Tetyana and her colleagues evacuated nearly all of the museum’s collection out of Kharkiv, the most heavily damaged of Ukraine’s major cities. She refuses to remove herself from the war’s lethal proximity. In late May, less than three miles from the museum, a Russian missile destroyed part of the publishing house that printed Vakulenko’s book, killing seven workers. The attack only intensified her devotion to the Ukrainian cause.

“I know I could die. But it’s not fatalism to stay — it’s my will,” she said. “This land created me. How could I live somewhere else?”

Etc.

— I’m grateful to two different groups for giving me the chance to talk about Ukraine in recent days. In Washington, D.C., I spoke alongside my friend Alex Horton, a Washington Post reporter, at a reunion for Stars and Stripes, the independent military newspaper that hired me in 2011 to cover the U.S. war in Afghanistan. In California, I met with the good folks of Democracy Winters, a nonpartisan network of volunteers dedicated to civic (and civil) engagement in this grand experiment called self-rule. Neither discussion is available online, but for any group looking for a speaker on Ukraine, I’m always willing to help — so long as travel to Russia or Belarus isn’t required.

— My sincere thanks for reading. Please share Reporting on Ukraine with anyone you know with an interest in the country, and if you’re a free subscriber and you like what you see, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to paid. You can also support my self-funded reporting here. Thank you.

Thanks Martin for this excellent reporting.

This is sad and fascinating. It's incredible to witness the (re)birth of a nation and culture's literary and artistic identity right before your eyes. But also so sad that so many have been targeted and killed. How tragic that Amelina played a role in unearthing Vakulenko's diary and saving it before she was killed herself. I read about the printing press in your previous substack. Do you think it was targeted specifically because it was printing books/literature?